This paper is also available in French. See Cahier Charles Fourier 20, Dec. 2009, p. 63-78, ill.

Cet article est publié en langue française dans le Cahier Charles Fourier 20, décembre 2009, p. 63-78, ill.

par Tippins, Sherill

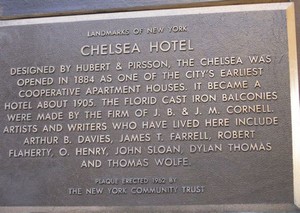

It is difficult to find an artist who has not heard of New York’s Chelsea Hotel. Since its doors opened in 1884, the eleven-story residence, occupying seven city lots on West Twenty-Third Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, has housed literally thousands of known and unknown writers, painters, musicians, filmmakers, dancers, and political activists, along with thousands more non-artists who have possessed what one resident called “the artistic attitude to life.” [1] Through those doors passed Thomas Wolfe, Dylan Thomas, Arthur Miller, Brendan Behan, Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Arman, Jean Tinguely, Andy Warhol, Miloš Forman, William Burroughs, Patti Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe, Abdullah Ibrahim, R. K. Narayan, and countless others.

Avec l’aimable autorisation de David Bard

Visitors who climb the Chelsea’s winding brass-and-marble staircase, flooded with light from the large rooftop skylight, are often overwhelmed by the feeling that the residue of earlier generations’ lives and work has somehow seeped into the building’s very walls. This time-stained quality has inspired a plethora of Chelsea Hotel ghost stories-not surprising in a building that attracts so many who live by their imaginations. In fact, there is a more interesting mystery at the heart of this haven for artists embedded in the heart of one of the world’s most commercial cities. The mystery is, how did the Chelsea become the largest and longest-lived creative community in America, if not in the entire world ?

Oddly, few of the Chelsea’s admirers or residents seem to have asked themselves this question. They rarely speculated whether the Chelsea was intentionally designed to serve as a creative nexus, or if it simply evolved serendipitously-one lucky accident after another. The hotel’s owners profess ignorance of the details of the building’s origins, and city records from the nineteenth century are sparse. As for the artist-residents, the composer Virgil Thomson frequently expressed his conviction that the Chelsea was from the beginning an artists’ residence [2] ; Arthur Miller noted its curious absence of class distinctions [3] ; and the Irish writer Ulick O’Connor praised it as “an extraordinary institution where you have the liberty to do anything you want.” [4] Yet even these men -who knew better than most that no workable creative community arises by chance, but rather by careful design- never dug deeper to discover how this unique phenomenon was born and what has enabled it to survive for 125 years and counting.

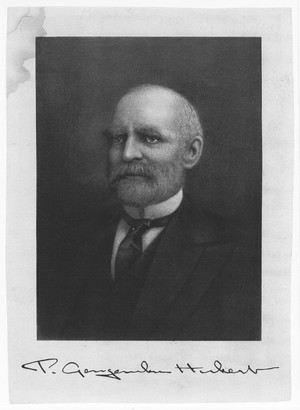

It is my contention that the Chelsea Hotel’s destiny as a world-class creative community was determined, indirectly, by the ideas of Charles Fourier, and that without Fourier’s influence the Chelsea phenomenon would not have occurred. In his book, The Utopian Alternative : Fourierism in Nineteenth-Century America, Carl J. Guarneri has pointed out that Philip Gengembre Hubert, the architect who designed the Chelsea, had ties to Fourierism that were “direct and familial.” [5] Hubert’s father, Colomb Gengembre, was the architect commissioned to design Fourier’s experimental Phalanx at Condé-sur-Vesgre in 1832. Despite the failure of that experiment, Gengembre’s enthusiasm for Fourier’s theory remained strong, and Philip, who was two at the time of the Condé-sur-Vesgre project, grew up steeped in Fourierist doctrine. Spending much of his childhood with his paternal grandfather, Philippe Gengembre -the liberal-minded inventor, engineer, and founder and director of the government ironworks at Indret- young Philip reached adulthood with a practical knowledge of architecture and engineering, a fascination with technology and an interest in inventing, and an abiding interest in improving conditions for the working classes. [6]

Like many other Fourierists, Colomb Gengembre fled France in the wake of the 1848 revolution, disgusted with the violent class warfare that appeared unlikely to end. He emigrated with his wife and three grown children -including Philip, aged 19- to Cincinnati, Ohio, where under his guidance his sons built a cabin for the family on the banks of the Ohio River. In his book, Victor Considerant, Jonathan Beecher describes Considerant’s visit to the Gengembre family in Ohio in 1853, where the former found Colomb still full of enthusiasm for the Fourierist movement, in touch with other Fourierists in the area, and convinced that despite recent reversals the United States remained the natural new home for the movement. [7] Soon after Considerant’s departure, Colomb moved to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, with his elder son, Henry. Philip, who had created a career for himself as a French language instructor, moved first to Philadelphia to teach, and then to Boston with his wife and growing family. By this time, both Henry and Philip had adopted their maternal grandmother’s English surname, Hubert -a name that Americans found easier than “Gengembre” to pronounce.

Wherever he went, Hubert impressed the Americans he encountered with his nimble intellect and his kindness. His status as a self-made man, combined with his genteel upbringing and ability to converse “with keen intelligence and originality upon politics, social science, invention and literature,” [8] easily won him a place in Boston’s intellectual circles. Like many of this group, he was abstemious in his personal habits, avoiding alcohol and red meat and spending his free time writing and staging amateur theatricals, sketching, and tinkering with inventions. By his mid-thirties Hubert had become such a sought-after instructor that he was offered an assistant professorship at Harvard. He might have accepted the offer had two events not occurred almost simultaneously to dissuade him : first, he sold a patent for one of his inventions -a “self-fastening button” for use on Union Army uniforms- for the staggering sum of $120,000, making him independently wealthy. Second, in Allegheny, his now socially-prominent father contributed, free of charge, plans for a new Allegheny City Hall -but when a city official offered to cut Colomb in on the graft he expected to collect through the building’s construction, the elderly Fourierist became so outraged and disenchanted with America that he vowed never to speak another word of English. He kept his promise until his death a year later, in 1863. [9]

Whether or not Colomb’s frustrated idealism, closely followed by his death, affected Philip’s decision to end his fifteen-year teaching career, his new wealth enabled him to move toward what he called a life of practical action. With the close of the Civil War, he moved his family to New York to begin a new life as an architect. Following an extended trip to Europe and Great Britain, where he was exposed to the latest ideas in architecture and, according to his descendants, may have studied architecture briefly at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, [10] he established a partnership in New York with the older, more experienced James Pirrson and embarked on the design of a number of neo-gothic churches and private homes.

But the level of graft that Colomb Gengembre had encountered in Pennsylvania was nothing compared to the record-breaking thefts then being carried out in New York by the infamous Senator William “Boss” Tweed. The discovery of millions of dollars in thefts, and the enormous financial burden they placed on the city -followed by the national recession of 1873- created a crisis in New York as deeply social as it was economic. As the city proved unable to pay its workers, strikes turned violent in the city’s upper reaches around Central Park. As unemployment spread, riots broke out on the Lower East Side. For the first time in that deeply divided, competitive, money-obsessed Gilded Age, New Yorkers gathered together in lecture halls -bakers sitting next to bankers, carpenters next to factory owners- to ask how they might begin to repair the torn economic and social fabric that they had allowed, through their own apathy, to be torn to shreds.

This drawing-together of socioeconomic classes was sufficiently remarkable to be noted by the press. The new sense of unity in the face of disaster brought back memories for some of the great recession of 1837, when Fourierism found its first foothold in the United States. Now, amidst this fresh wave of anxiety, a number of prominent American Fourierists and other communitarians -including Charles Dana, George William Curtis, Horace Greeley and John Noyes- began to review in print their 1840s phalanstery experience and to debate how Fourierist communities might be revived and improved in the present time. Greeley suggested that communities be more selective in admitting new members, to minimize the number of trouble-makers and idlers weighing down the delicate young collectives with their demands. John Noyes recommended avoiding agricultural labor and instead concentrating on “the centers of business” where they could find tools and trade and take their place “at the front of the general march of improvement.” [11] As for the overall prognosis for communal life, Greeley concluded :

“I shall be sorely disappointed if this Nineteenth Century does not witness its very general adoption as a means of reducing the cost and increasing the comfort of the poor man’s living... I am convinced...that the Social Reformers are right on many points...and I deem Fourier -though in many respects erratic, mistaken, visionary- the most suggestive and practical among them.” [12]

Hubert, whose architectural firm had been shut down by the recession from 1876 to 1879, had plenty of time to read such musings and to consider how he might use his own experience and talent to help solve New York’s problems. Surely, the tools of phalanstery life, created in France during a similar time of upheaval, could be used to address two of the city’s most critical issues : social atomization and the lack of affordable housing that caused such suffering for the working poor and was threatening to extinguish the city’s “harmonizing” middle class. The challenge lay in presenting Fourier’s ideas in a manner acceptable to mainstream New Yorkers-avoiding association with the dreaded word, “socialism,” which struck fear of class warfare in American hearts.

At his country retreat in Connecticut, Hubert created a proposal for the construction of urban residential cooperatives-giving them the name “Hubert’s Home Club Associations.” Unlike the French, he wrote in his brochure, New Yorkers were burdened with “the need to segregate themselves economically to define their status.” [13] To prove their superiority to tenement dwellers or boardinghouse tenants, families spent their lives in dark, overpriced townhouses, isolated even from those of their own social class. Apartment houses, introduced only ten years earlier, still struck most New Yorkers as unacceptably exotic. Those who considered living in one had to choose between so-called “French flats” -narrow, dark railroad flats with one room opening into the next, front to back, and sunlight entering only from the windows at each end- or hugely overpriced, “aesthetically-designed” buildings in expensive neighborhoods whose exterior decoration and pretentious names were aimed at reassuring purchasers of their respectability. By acting cooperatively, Hubert explained, Association members would be able to create their own building -designing it to suit their needs and realizing huge savings by sharing the costs of land, building construction, home maintenance, and fuel.

Describing these Associations as merely business arrangements -that he “earnestly protest[ed] against any socialistic union” [14]- Hubert assured prospective applicants that each club would consist of families of “congenial tastes” and “similar social and economic positions.” [15] Nevertheless, his free use of other Fourierist ideas, such as the joint-stock corporate structure and the shared ownership of a single residential building, promised to serve as a first step toward bringing New Yorkers together in a new, productive way.

And just as Greeley had hoped, Hubert first addressed the “poor man’s” needs -by designing a prototype cooperative on unfashionable 80th Street for the population of underpaid clerks and other young office workers then pouring into the city. His cooperative’s eight light-filled, three-bedroom apartments, equipped with the latest technology, far outstripped anything a clerk could ordinarily afford. Yet each was priced at only $4,000 -roughly half the price of similar-sized apartments- and, with a mortgage, buyers needed only a $1,500 down payment. The purchase price would be refunded by the savings in rent in less than four years -and unlike renters, Home Club members could sell their apartments at any time, recouping their investment and even pocketing the profits. [16]

Fourier himself had once suggested that experimental phalanxes created for the poorer classes would attract the middle class as soon as their advantages became evident [17]-and that is exactly what happened with this first Home Club Association. When less well-off New Yorkers hesitated, suspicious of a deal that seemed too good to be true, better-off families rushed to invest in Hubert’s Home Club plan. Reluctantly, the architect gave in to middle-class demand, but he later wrote of his deep regret over this failure to begin to solve one of the most crucial problems of the city’s working poor.

To others, however, Hubert’s Home Club idea seemed a great success, and his firm was besieged with requests to create more Associations. For Jared B. Flagg, a wealthy portraitist and real estate speculator with land on fashionable Fifty-Seventh Street next door to the current site of Carnegie Hall, Hubert designed The Rembrandt, a Home Club for well-to-do artists with luxurious twelve-room apartments connected to double-height studios -the city’s first duplexes. This time, Hubert added several rental units whose income would help cover the building’s maintenance costs. Before construction was even completed, the shareholder-owners began receiving offers for their apartments at twice the original price.

Next came the Hawthorne, a lodge-like cooperative with wood-beamed ceilings on West Fifty-Ninth Street facing Central Park [18], and then the Hubert, the Milano, the Mount Morris, No. 80 Madison Avenue, and No. 121 Madison -all of which attracted members of the professional class, for the most part- followed by a rural Connecticut cooperative that Hubert designed as a country retreat. [19] Finally, in 1883, in partnership with Jose F. de Navarro, a former Jesuit teacher from Spain who had made a fortune building one of New York’s new elevated railroad lines, Hubert designed the Central Park Apartments -a cooperative for New York’s upper-class. Also known as the Navarro Flats, this veritable Versailles of cooperatives, consisting of twelve palatial ten-story buildings arranged in a large square around a landscaped central courtyard, provided more space for entertaining than even the grandest private mansions and glorious views of Central Park. [20]

All of these cooperatives were huge, by 1880s building standards -occupying multiple lots and rising eight to ten stories high when few other buildings were higher than five. As a result, within just a few years, Hubert’s cooperatives began to alter the look of the city itself to a noticeable degree, with their signature style -Queen Anne mixed with Victorian Gothic-featuring multiple towers, peaked roofs, dormers, enormous bay windows, and outdoor galleries that connected apartments with one another. Politic as Hubert had been in his neutral presentation of the benefits of cooperative living, the buildings themselves powerfully expressed the potential social benefits of “the enlargement of home-the extension of family union beyond the little man-and-wife circle” [21] -a notion foreign to most Americans’ staunchly independent way of thinking. Still, as Guarneri has pointed out, with no mixing of social classes or sharing of domestic duties, little of Fourier’s plan survived in these group residences aside from this visual testimony. [22]

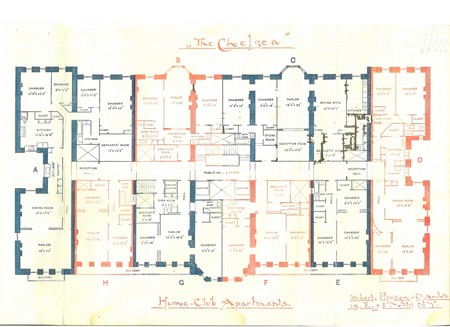

With his next project, however -the Chelsea Association Building- Hubert would take his cooperative experiment significantly further. Again, a death in the family preceded this change in direction. Shortly after he purchased the seven contingent lots on West Twenty-Third Street (plus a townhouse to the rear, facing Twenty-Second Street, to be used as servants’ quarters), Hubert’s wife, Cornelia, died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage, leaving him with only his twenty-five-year-old daughter, the aspiring actress Marie, at home. [23] Whether this unexpected tragedy prompted thoughts of Hubert’s own mortality or caused him to rethink his priorities can never be known. What is known is that whereas one newspaper report filed in the early months of the Chelsea’s construction described the building as slated to contain forty apartments -that is, only four large apartments sharing each 14,000-square-foot residential floor- by the end of its completion the plan had been altered to create twice that number of units of widely varying sizes and prices.

By summer, 1884, rambling apartments of up to 3,000 square feet wrapped around the east and west ends of each floor of the tall, rectangular building, itself 175 feet wide and 80 feet deep.

Toward the center of each floor, nearer the elevators and central stairwell, Hubert placed smaller three- or four-room apartments as small as 800 square feet. The larger apartments, featuring three or four bedrooms, dining rooms, parlors, reception halls, and large kitchens, sold for roughly $8,000 each. The smaller suites, with one to three bedrooms and lacking a full kitchen, were priced as low as $2,400-significantly less even than the office-workers’ apartments which Hubert had designed several years before. [24] On the top floor, a row of seven art studios ran along the front of the building, facing north, while eight apartment-studio duplexes occupied the rear, their upper-floor studios jutting up through the Chelsea’s roof so that they, too, could capture an abundance of northern light. Apartments could be combined or divided at shareholders’ request, and the interior design was completed to each owner’s taste, adding even greater diversity to a building whose array of apartment sizes and prices was already unprecedented in this city of strict economic segregation. As with the Rembrandt, Hubert saw to it that a substantial number of apartments were reserved as rental properties whose income, along with that of the ground-floor shops, would subsidize the building’s maintenance costs, while at the same time introducing a stimulating flow of transient residents mixing with owners on all floors.

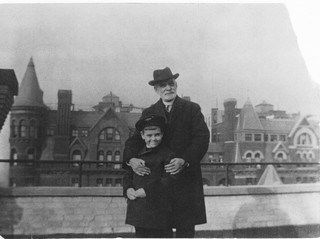

It is interesting to note that this total number of eighty apartments corresponded to the minimum number of eighty families which Fourier considered necessary for the establishment of an experimental phalanstery. With walls between apartments three feet thick, and central corridors eight feet wide -wide enough to resemble a city street, Hubert wrote- families were guaranteed privacy within their individual, light-filled, well-proportioned homes. Yet, to a much greater degree than in his earlier cooperatives, Hubert also provided numerous spaces for social interaction -including three elegant, linked communal dining rooms for residents on the ground floor with a large kitchen and extensive wine cellar in the basement ; a comfortable, lodge-like ground-floor lobby and ornate ladies’ sitting room near the entrance ; a basement billiards room for male residents ; and a spectacular roof garden with a wide, brick-paved promenade running the width of the rear half of the building. As a final touch, Hubert added to the roof a striking pyramid-shaped penthouse front and center, enhanced by a private garden, huge fireplace, and enormous north-facing windows, to be used as an “at-home” clinic so that residents need not leave their family and friends when they were ill. [25]

While it would have been unrealistic to expect New Yorkers to share domestic chores, servants housed in the townhouse behind the Chelsea were shared by all. Bulk purchases lowered the price of meals and fuel, both of which were provided to shareholders at near-cost. And of course, the Chelsea boasted every possible modern convenience from speaking tubes to steam heating, safety elevators to electric lights, dumbwaiters for delivering meals upstairs to a telephone in the manager’s office-as one would expect in a cooperative designed by a son of Fourier’s 1830s band of French technophiles.

Just as the Chelsea’s physical and economic design resembled in many ways those of a standard phalanstery, so the social makeup of its Association echoed that recommended by Fourier for a phalanx in its infancy : a central core of cultivators and manufacturers, a smaller population of capitalists, scholars, and artists for the sake of economic survival, psychological balance, and spiritual growth ; and a Board of Directors manned by the wealthiest and most knowledgeable members of the cooperative. [26] At the Chelsea, located not in the country but in the midst of an urban environment then under massive construction, the “cultivators and manufacturers” were represented by real estate developers, builders, and contractors then involved in the creative process of “growing” the city -in this case including most of the people who literally built, equipped, and decorated the Chelsea itself. The “capitalists, scholars, and artists” included not only by the painters and sculptors in the fifteen top-floor studios, but by a number of musicians, actors, authors, professors, bibliophiles, financiers, and wealthy philanthropists who lived downstairs. And with a founding Board of Directors that included a well-known stockbroker, a former president of the Merchants and Traders’ Exchange, a future governor of Virginia, and the president of the company that installed the Chelsea’s innovative, patented roof, the call for a wealthy and knowledgeable leadership had been answered as well.

With an eighty-family building and a reasonably diverse population, the Chelsea stood poised to take its place, as John Noyes had recommended, “at the front of the general march of improvement.” But the question remained : how would it go about doing this ? What kind of work was to be accomplished here ?

The answer seems to lie in the Fourierist notion of art social -the importance assigned to the role of artists in unifying a diverse population and guiding it forward in its evolution. Hints of this intention lie not only in the provision of fifteen art studios occupying the Chelsea’s entire top floor, but also in the pronounced presence of nature themes in its décor-stained-glass transoms displaying images of seashells and flowers, etched-glass door panels featuring forest scenes, hand-carved wood fireplace mantels and hand-painted tiles, a lobby hung with paintings of the Hudson River school, and exquisite wrought-iron sunflowers adorning its exterior balconies and central stairway -the latter evoking a dream of the liberated American artist as vividly as Fourier’s Crown Imperial flower represented the downtrodden artist in “civilization.”

Surely it was no coincidence that Hubert located his Chelsea cooperative in the center of what was then New York’s arts district, on a street crowded with theaters, music halls, art academies and lecture halls. Also significant is the architect’s decision to build the Lyceum, a cooperative theater, thee blocks east of the Chelsea even as the residential cooperative was under construction. In August, 1884, as the Chelsea Association Building’s first residents prepared to move in, Hubert handed over control of the Lyceum to a team of young, ambitious theater professionals -Franklin Sargent, David Belsaco, Steele MacKaye, and the Frohman brothers- all vocal proponents of naturalist theater who, in the years to come, would create the first real American indigenous theater movement.

In connection with the theater, Hubert created the Lyceum School of Drama -New York’s first successful academy for actors- open to male and female students, rich and poor alike. In time, the Lyceum Theater would be relocated to Times Square and the Lyceum School would be renamed the American Academy of Dramatic Arts -but both institutions still operate today.

With his own urban Fourierist-style “phalanstery” and accompanying “opera house” in place, Philip Hubert himself moved into the Chelsea when it opened on October 1st, 1884. There, he set to work on a naturalist play about the Salem witch trials, relying on the actual trial transcripts for dialogue. His daughter Marie, who shared his home at the Chelsea, married Gustav Frohman, manager of the Lyceum. In time, her husband would produce her father’s play, The Witch [27] and Marie would tour the nation as its star.

Hubert considered The Chelsea Association -with its builders and financiers, professional men and entrepreneurs, wealthy retired couples and young men-about-town, newlyweds, artisans, and artists, writers, musicians, and students of the arts- , his most successful Home Club. David Croly, editor of the New York trade journal, the Real Estate Record, and a well-known promoter of the philosophy of Auguste Comte, praised it as representing "a new way of living, something more than a mere desire to enjoy greater material advantages." [28] An anonymous writer in Charles Dana’s New York Sun urged every other New York architect to "build tremendous stairs for the brave one hundred ; splendid cities with pillars and arcades..." and to "never forget that he is working for an entity that is more sacred and more powerful than any one human being can be, for a corporation or at least a congerie of individuals..." [29]

Yet the year after the Chelsea was completed, new residential buildings of its size were banned -ostensibly due to safety concerns, though it appears likely, since no disasters had occurred and large hotels were not included in the ban, that city officials were motivated at least in part by fear of socialist foment. The following year, 1886, Philip Hubert responded by becoming the largest financial backer of single-taxer Henry George’s campaign for New York mayor on the United Labor Party ticket. Following George’s defeat, Hubert gave up on his New York cooperative idea and moved to Los Angeles, where he spent the rest of his life designing small homes and labor-saving devices for the working poor.

In his absence, the Chelsea survived as a kind of romantic-socialist village in the midst of a capitalist American metropolis, providing the basic needs of any creative community, utopian or not : relatively low housing costs, stimulating company, sufficient privacy, high tolerance for variations in personality and behavior, respect for creative work and for artists’ social function, and easy access to the market and to other outlets for self-expression. While there is no evidence that Hubert ever used the words “phalanstery,” “Fourier,” or “socialism” in connection with the Chelsea or any of his other New York cooperatives, the Chelsea demonstrates how, under certain conditions and with a little luck, architectural design can contribute significantly to social destiny. Evidently, Hubert agreed with the anonymous editor of the New York Journal, Manufacturer and Builder, who wrote in 1871, “[A]fter all this hobby-riding of the so-called thinkers, the true problems of the century are its material and economical ones. Improve the physical conditions under which humanity exists, and humanity may be safely left to improve itself -so intimately dependent on material conditions is the science of social status.” [30]

In fact, it is astonishing to see how many Chelsea Hotel artists have demonstrated a deep engagement in social issues through the ensuing decades, whether directly as activists or indirectly as members of the avant-garde. At the Chelsea, the prominent editor William Dean Howells read the galleys of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward and changed his attitude toward the role of literature in creating social change. In Room 829, Thomas Wolfe, awakened by the Depression to the importance of social issues, brilliantly conveyed the psychological impact of economic suffering in You Can’t Go Home Again. At a luncheon in one of the residents’ dining rooms, Jackson Pollock vomited under the pressure of presenting his work to a gaggle of war-enriched collectors assembled by Peggy Guggenheim. As president of PEN International, Arthur Miller invited Cold-War-era Soviet and Eastern European writers to stay at the Chelsea as his guest. Andy Warhol encouraged his subjects to defy commercial convention and to look at themselves as fully-realized works of art. Harry Smith taught Abbie Hoffman techniques for creating political theater. And the list goes on and on. From the nineteenth century to the twenty-first, the Chelsea Hotel artists have fulfilled the task defined for them in 1830s Paris : to use their special sensitivity in the service of their community -to engage the emotions of the people and thereby make them one.

As the writer Félix Pyat wrote as long ago as 1834 in France, “Art has almost become a cult, a new religion which is arriving just in time, when gods and kings are disappearing.” [31] In New York as well, the Chelsea Association Building, with its rich, diverse population and wide array of gifted artists, arrived just in time. Perhaps that is why one can still feel the spirit of Charles Fourier haunting its bricks and stone.